by Leon Pantenburg

|

| Andersonville was one of many horrific Civil War prisons. |

When Dr. John Leach, published the groundbreaking "Survival Psychology" in 1982, he relied on a wide range of sources, including journals and diaries from the Civil War. "John Ransom's Andersonville Diary" was one of those sources, and Ransom's work is one of the first records of what it takes to develop a survivor attitude.

Leach studied survivors' reactions from many different disasters. Distilled down to one sentence, Leach's research found: Psychological responses to emergencies follow a pattern. In the case of John Ransom, we can learn a lot from a prisoner of war.

Prison camps

Ransom, brigade quartermaster of the Ninth Michigan Calvary, was 20 years old when he was captured in eastern Tennessee in 1863. He was first sent to the prison at Belle Isle, Virginia and then to Andersonville, Georgia.

Civil War prisons on both sides were hell holes. Best estimates, according to the book introduction, is that the Confederacy imprisoned, over-all, about 194,000 soldiers, of whom 36,400 died. The Union held some 220,000 Confederates, of whom 30,150 died.

Camp Sumpter at Andersonville, was among the worst.

Andersonville was one of the largest Confederate military prisons during the Civil War. During the 14 months the prison existed, according to the National Park Service, more than 45,000 Union soldiers were confined here. Of these, almost 13,000 died here.

The pen initially covered about 16-1/2 acres of land enclosed by a 15-foot high stockade of hewn pine logs. It was enlarged to 26- 1/2 acres in June of 1864. Flowing through the prison yard was a stream called Stockade Branch, which supplied water to most of the prison. The first prisoners

were brought to Andersonville in February, 1864, according to the park service. During the next few months approximately 400 more arrived each day until, by the end of June, some 26,000 men were confined in a prison area originally intended to hold 13,000. The largest number held at any one time was more than 32,000 in August, 1864.

Survival situations bring out a variety of reactions, Leach writes, including some that make the situation worse. Leach's studies show that only 10 to 15 percent of any group involved in any emergency will react appropriately. Another 10 to 15 percent will behave totally inappropriately and the remaining 70 to 80 percent will need to be told what to do.

The most common reaction at the onset of an emergency is disbelief and denial.

Here’s the typical disaster reaction progression, according to “Survival Psychology” and how it played out in Andersonville:

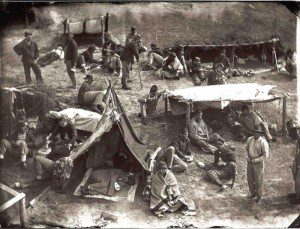

|

| This 1994 recreation shows how the camp might have looked. (National Park service photo) |

*Denial: The first reaction will probably be: “This can’t be happening to me!” This disbelief can cause people to stand around, doing nothing to save themselves. The 80 percenters in any survival situation will have to be ordered to help themselves.

Ransom noticed this bewilderment among newcomers to the prison pen. Some were literally frozen in place, making them easy prey for gangs of robbers.

"All are considerably surprised to find themselves in quite so bad a place," Ransom writes, and he mentions that many were incredulous they were supposed to live under those circumstances.

"A new prisoner fainted away at his entrance to Andersonville, and is now crazy, a raving maniac," he adds.

Another prisoner, Robert H. Kellogg, wrote about this denial at Andersonville in his book "Life and Death in Rebel Prisons":

"As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. "Can this be hell?" "God protect us!" and all thought that He alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. .. how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then."

*Hypoactivity, defined as a depressed reaction; or hyperactivity, an intense but undirected liveliness: The depressed person will not look after himself or herself, Leach writes, and will probably need to be told what to do. The hyperactive response can be more dangerous because the affected person may give a misleading impression of purposefulness and leadership.

Many prisoners reached these states, Ransom writes, and would do crazy things. One man threw away all his clothing and possessions, Ransom observed, and walked around in a daze. Conversely, many would sink into deep depression, not take care of themselves and just die.

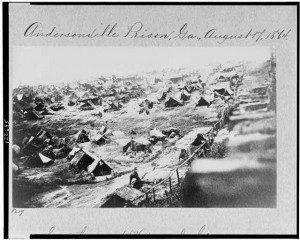

|

| Andersonville, August 1864 |

*Stereotypical behavior: This is a form of denial in which victims fall back on learned behavior patterns, no matter how inappropriate they are. The Boss may decide to continue in that role, even though he/she has no idea of what to do. Sadly, the underling may also revert to that subordinate role, even though he/she may be better prepared mentally.

This was a frequent occurrence, Ransom noted. Groups of solders would form "messes," frequently based on familiar squad structures. A sergeant might not have any skills in building a shelter or cooking under primitive conditions, but still end up as the leader.

"Being in these conditions brings out a man for just what he is worth," Ransom writes. " Those whom we expect the most from in the way of braving hardships and dangers, prove to be nobody at all. And very often those whom we we expect the least from prove to be heroes every inch of them."

Anger: A universal reaction, anger is irrational.

Psychological breakdown: This could be the most desperate problem facing a victim, and this stage is characterized by irritability, lack of interest, apprehension, psycho-motor retardation and confusion. Once this point is reached, the ultimate consequence may be death

Ransom and his comrades realized they were going to need a survival plan if any of them were to survive. They organized themselves immediately, and established a protocol for living in the prison.

By day three in Andersonville, Ransom's mess had already made rules:

"In our mess, we have established regulations, and any one not conforming with the rules is to be turned out of the tent. Must take plenty of exercise, keep clean, free as circumstances will permit of vermin, drink no water until it is boiled, which process purifies and makes it more healthy, are not to allow ourselves to get despondent, and must talk, laugh and make as light of our affairs as possible. Sure death for a person to give up and lose all ambition."

Sanitation in the crowded, filthy compound was critical, Ransom writes, and was incredibly important to survival.

"Some men are very filthy, which makes it disagreeable for those with more cleanly habits," he writes. "I believe that many, very many, who now die, would live if they adopted the rules that our mess has, and lived up to them. It is the only way to get along."

But the attitude that got Ransom through his captivity was one of optimism.

"Have been reading over the diary, and find nothing but grumbling and growlings. Had best enumerate some of the better things of this life. I am able to walk around the prison, though quite lame. Have black pepper to put in our soups. Am as clean, perhaps, as any here, with good friends to talk cheerful to. Am probably as well off as any here...and I should be thankful, and am thankful."

Order your copy of "John Ransom's Andersonville Diary" here.

No comments:

Post a Comment